WORLD WAR HISTORY

World War I (or the First World War, often abbreviated as WWI or WW1; German: Erster Weltkrieg) was a global war originating in Europe that lasted from 28 July 1914 to 11 November 1918. Contemporaneously known as the Great War or "the war to end all wars",[7] it led to the mobilisation of more than 70 million military personnel, including 60 million Europeans, making it one of the largest wars in history.[8][9] It is also one of the deadliest conflicts in history,[10] with an estimated 9 million combatant deaths and 13 million civilian deaths as a direct result of the war,[11] while resulting genocides and the related 1918 Spanish flu pandemic caused another 17–100 million deaths worldwide,[12][13] including an estimated 2.64 million Spanish flu deaths in Europe and as many as 675,000 Spanish flu deaths in the United States.[14]

On 28 June 1914, Gavrilo Princip, a Bosnian Serb Yugoslav nationalist and member of the Serbian Black Hand military society, assassinated the Austro-Hungarian heir Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo, leading to the July Crisis.[15][16] In response, Austria-Hungary issued an ultimatum to Serbia on 23 July. Serbia's reply failed to satisfy the Austrians, and the two moved to a war footing. A network of interlocking alliances enlarged the crisis from a bilateral issue in the Balkans to one involving most of Europe. By July 1914, the great powers of Europe were divided into two coalitions: the Triple Entente, consisting of France, Russia, and Britain; and the Triple Alliance of Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Italy. The Triple Alliance was only defensive in nature, allowing Italy to stay out of the war until April 1915, when it joined the Allied Powers after its relations with Austria-Hungary deteriorated.[17] Russia felt it necessary to back Serbia, and approved partial mobilisation after Austria-Hungary shelled the Serbian capital of Belgrade, which was a few miles from the border, on 28 July.[18] Full Russian mobilisation was announced on the evening of 30 July; the following day, Austria-Hungary and Germany did the same, while Germany demanded Russia demobilise within twelve hours.[19] When Russia failed to comply, Germany declared war on Russia on 1 August in support of Austria-Hungary, the latter following suit on 6 August; France ordered full mobilisation in support of Russia on 2 August.[20]

Germany's strategy for a war on two fronts against France and Russia was to rapidly concentrate the bulk of its army in the West to defeat France within 6 weeks, then shift forces to the East before Russia could fully mobilise; this was later known as the Schlieffen Plan.[21] On 2 August, Germany demanded free passage through Belgium, an essential element in achieving a quick victory over France.[22] When this was refused, German forces invaded Belgium on 3 August and declared war on France the same day; the Belgian government invoked the 1839 Treaty of London and, in compliance with its obligations under this treaty, Britain declared war on Germany on 4 August. On 12 August, Britain and France also declared war on Austria-Hungary; on 23 August, Japan sided with Britain, seizing German possessions in China and the Pacific. In November 1914, the Ottoman Empire entered the war on the side of Austria-Hungary and Germany, opening fronts in the Caucasus, Mesopotamia, and the Sinai Peninsula. The war was fought in (and drew upon) each power's colonial empire also, spreading the conflict to Africa and across the globe. The Entente and its allies eventually became known as the Allied Powers, while the grouping of Austria-Hungary, Germany and their allies became known as the Central Powers.

The German advance into France was halted at the Battle of the Marne and by the end of 1914, the Western Front settled into a war of attrition, marked by a long series of trench lines that changed little until 1917 (the Eastern Front, by contrast, was marked by much greater exchanges of territory). In 1915, Italy joined the Allied Powers and opened a front in the Alps. Bulgaria joined the Central Powers in 1915 and Greece joined the Allies in 1917, expanding the war in the Balkans. The United States initially remained neutral, though even while neutral it became an important supplier of war materiel to the Allies. Eventually, after the sinking of American merchant ships by German submarines, the declaration by Germany that its navy would resume unrestricted attacks on neutral shipping, and the revelation that Germany was trying to incite Mexico to initiate war against the United States, the U.S. declared war on Germany on 6 April 1917. Trained American forces did not begin arriving at the front in large numbers until mid-1918, but the American Expeditionary Force ultimately reached some two million troops.[23]

Though Serbia was defeated in 1915, and Romania joined the Allied Powers in 1916 only to be defeated in 1917, none of the great powers were knocked out of the war until 1918. The 1917 February Revolution in Russia replaced the Monarchy with the Provisional Government, but continuing discontent with the cost of the war led to the October Revolution, the creation of the Soviet Socialist Republic, and the signing of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk by the new government in March 1918, ending Russia's involvement in the war. Germany now controlled much of eastern Europe and transferred large numbers of combat troops to the Western Front. Using new tactics, the German March 1918 Offensive was initially successful. The Allies fell back and held. The last of the German reserves were exhausted as 10,000 fresh American troops arrived every day. The Allies drove the Germans back in their Hundred Days Offensive, a continual series of attacks to which the Germans had no reply.[24] One by one the Central Powers quit: first Bulgaria (September 29), then the Ottoman Empire (October 31) and the Austro-Hungarian empire (November 3). With its allies defeated, revolution at home, and the military no longer willing to fight, Kaiser Wilhelm abdicated on 9 November and Germany signed an armistice on 11 November 1918, ending the war.

World War I was a significant turning point in the political, cultural, economic, and social climate of the world. The war and its immediate aftermath sparked numerous revolutions and uprisings. The Big Four (Britain, France, the United States, and Italy) imposed their terms on the defeated powers in a series of treaties agreed at the 1919 Paris Peace Conference, the most well known being the German peace treaty: the Treaty of Versailles.[25] Ultimately, as a result of the war, the Austro-Hungarian, German, Ottoman, and Russian Empires ceased to exist, and numerous new states were created from their remains. However, despite the conclusive Allied victory (and the creation of the League of Nations during the Peace Conference, intended to prevent future wars), a second world war followed just over twenty years later.

Etymology[edit]

Despite occurring in November of the Gregorian calendar, the event is most commonly known as the "October Revolution" (Октябрьская революция) because at the time Russia still used the Julian calendar. The event is sometimes known as the "November Revolution", after the Soviet Union modernized its calendar.[3][4][5] To avoid confusion, both O.S and N.S. dates have been given for events. For more details see Old Style and New Style dates.

At first, the event was referred to as the "October Coup" (Октябрьский переворот) or the "Uprising of the 3rd," as seen in contemporary documents (for example, in the first editions of Lenin's complete works).

Background[edit]

February Revolution[edit]

The February Revolution had toppled Tsar Nicholas II of Russia and replaced his government with the Russian Provisional Government. However, the provisional government was weak and riven by internal dissension. It continued to wage World War I, which became increasingly unpopular. There was a nationwide crisis affecting social, economic, and political relations. Disorder in industry and transport had intensified, and difficulties in obtaining provisions had increased. Gross industrial production in 1917 decreased by over 36% of what it had been in 1914. In the autumn, as much as 50% of all enterprises in the Urals, the Donbas, and other industrial centers were closed down, leading to mass unemployment. At the same time, the cost of living increased sharply. Real wages fell to about 50% of what they had been in 1913. By October 1917, Russia's national debt had risen to 50 billion rubles. Of this, debts to foreign governments constituted more than 11 billion rubles. The country faced the threat of financial bankruptcy.

Unrest by workers, peasants, and soldiers[edit]

Throughout June, July, and August 1917, it was common to hear working-class Russians speak about their lack of confidence in the Provisional Government. Factory workers around Russia felt unhappy with the growing shortages of food, supplies, and other materials. They blamed their managers or foremen and would even attack them in the factories. The workers blamed many rich and influential individuals for the overall shortage of food and poor living conditions. Workers saw these rich and powerful individuals as opponents of the Revolution, and called them "bourgeois", "capitalist", and "imperialist".[6]

In September and October 1917, there were mass strike actions by the Moscow and Petrograd workers, miners in the Donbas, metalworkers in the Urals, oil workers in Baku, textile workers in the Central Industrial Region, and railroad workers on 44 railway lines. In these months alone, more than a million workers took part in strikes. Workers established control over production and distribution in many factories and plants in a social revolution.[7] Workers organized these strikes through factory committees. The factory committees represented the workers and were able to negotiate better working conditions, pay, and hours. Even though workplace conditions may have been increasing in quality, the overall quality of life for workers was not improving. There were still shortages of food and the increased wages workers had obtained did little to provide for their families.[6]

By October 1917, peasant uprisings were common. By autumn, the peasant movement against the landowners had spread to 482 of 624 counties, or 77% of the country. As 1917 progressed, the peasantry increasingly began to lose faith that the land would be distributed to them by the Social Revolutionaries and the Mensheviks. Refusing to continue living as before, they increasingly took measures into their own hands, as can be seen by the increase in the number and militancy of the peasant's actions. From the beginning of September to the October Revolution there were over a third as many peasant actions than since March. Over 42% of all the cases of destruction (usually burning down and seizing property from the landlord's estate) recorded between February and October occurred in October.[8] While the uprisings varied in severity, complete uprisings and seizures of the land were not uncommon. Less robust forms of protest included marches on landowner manors and government offices, as well as withholding and storing grains rather than selling them.[9] When the Provisional Government sent punitive detachments, it only enraged the peasants. In September, the garrisons in Petrograd, Moscow, and other cities, the Northern and Western fronts, and the sailors of the Baltic Fleet declared through their elected representative body Tsentrobalt that they did not recognize the authority of the Provisional Government and would not carry out any of its commands.[10]

Soldiers' wives were key players in the unrest in the villages. From 1914 to 1917, almost 50% of healthy men were sent to war, and many were killed on the front, resulting in many females being head of the household. Often—when government allowances were late and were not sufficient to match the rising costs of goods—soldiers' wives sent masses of appeals to the government, which went largely unanswered. Frustration resulted, and these women were influential in inciting "subsistence riots"—also referred to as "hunger riots," "pogroms," or "baba riots." In these riots, citizens seized food and resources from shop owners, who they believed to be charging unfair prices. Upon police intervention, protesters responded with "rakes, sticks, rocks, and fists."[11]

Antiwar demonstrations[edit]

In a diplomatic note of 1 May, the minister of foreign affairs, Pavel Milyukov, expressed the Provisional Government's desire to continue the war against the Central Powers "to a victorious conclusion", arousing broad indignation. On 1–4 May, about 100,000 workers and soldiers of Petrograd, and, after them, the workers and soldiers of other cities, led by the Bolsheviks, demonstrated under banners reading "Down with the war!" and "All power to the soviets!" The mass demonstrations resulted in a crisis for the Provisional Government.[12] 1 July saw more demonstrations, as about 500,000 workers and soldiers in Petrograd demonstrated, again demanding "all power to the soviets," "down with the war," and "down with the ten capitalist ministers." The Provisional Government opened an offensive against the Central Powers on 1 July, which soon collapsed. The news of the offensive's failure intensified the struggle of the workers and the soldiers. A new crisis in the Provisional Government began on 15 July.[citation needed]

July days[edit]

On 16 July, spontaneous demonstrations of workers and soldiers began in Petrograd, demanding that power be turned over to the soviets. The Central Committee of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party provided leadership to the spontaneous movements. On 17 July, over 500,000 people participated in what was intended to be a peaceful demonstration in Petrograd, the so-called July Days. The Provisional Government, with the support of Socialist-Revolutionary Party-Menshevik leaders of the All-Russian Executive Committee of the Soviets, ordered an armed attack against the demonstrators, killing hundreds.[13]

A period of repression followed. On 5–6 July, attacks were made on the editorial offices and printing presses of Pravda and on the Palace of Kshesinskaya, where the Central Committee and the Petrograd Committee of the Bolsheviks were located. On 7 July, the government ordered the arrest and trial of Vladimir Lenin, who was forced to go underground, as he had done under the Tsarist regime. Bolsheviks were arrested, workers were disarmed, and revolutionary military units in Petrograd were disbanded or sent to the war front. On 12 July, the Provisional Government published a law introducing the death penalty at the front. The second coalition government was formed on 24 July, chaired by Alexander Kerensky.[14]

In response to a Bolshevik appeal, Moscow's working class began a protest strike of 400,000 workers. They were supported by strikes and protest rallies by workers in Kiev, Kharkov, Nizhny Novgorod, Ekaterinburg, and other cities.

Kornilov affair[edit]

In what became known as the Kornilov affair, General Lavr Kornilov, who had been Commander-in-Chief since 18 July, with Kerensky's agreement directed an army under Aleksandr Krymov to march toward Petrograd to restore order.[15] Details remain sketchy, but Kerensky appeared to become frightened by the possibility that the army would stage a coup, and reversed the order. By contrast, historian Richard Pipes has argued that the episode was engineered by Kerensky.[16] On 27 August, feeling betrayed by the government, Kornilov pushed on towards Petrograd. With few troops to spare at the front, Kerensky turned to the Petrograd Soviet for help. Bolsheviks, Mensheviks, and Socialist Revolutionaries confronted the army and convinced them to stand down.[17] The Bolsheviks' influence over railroad and telegraph workers also proved vital in stopping the movement of troops. Right-wingers felt betrayed, and the left-wing was resurgent.

With Kornilov defeated, the Bolsheviks' popularity in the soviets grew significantly, both in the central and local areas. On 31 August, the Petrograd Soviet of Workers and Soldiers Deputies—and, on 5 September, the Moscow Soviet Workers Deputies—adopted the Bolshevik resolutions on the question of power. The Bolsheviks won a majority in the soviets of Briansk, Samara, Saratov, Tsaritsyn, Minsk, Kiev, Tashkent, and other cities.

German support[edit]

Vladimir Lenin, who had been living in exile in Switzerland, with other dissidents organized a plan to negotiate a passage for them through Germany, with whom Russia was then at war. Recognizing that these dissidents could cause problems for their Russian enemies, the German government agreed to permit 32 Russian citizens, among them Lenin and his wife, to travel in a sealed train carriage through their territory. According to Deutsche Welle:

Insurrection[edit]

Planning[edit]

On 10 October 1917 (O.S.; 23 October, N.S.), the Bolsheviks' Central Committee voted 10–2 for a resolution saying that "an armed uprising is inevitable, and that the time for it is fully ripe."[19] At the Committee meeting, Lenin discussed how the people of Russia had waited long enough for "an armed uprising," and it was the Bolsheviks' time to take power. Lenin expressed his confidence in the success of the planned insurrection. His confidence stemmed from months of Bolshevik buildup of power and successful elections to different committees and councils in major cities such as Petrograd and Moscow.[20]

The Bolsheviks created a revolutionary military committee within the Petrograd soviet, led by the soviet's president, Trotsky. The committee included armed workers, sailors, and soldiers, and assured the support or neutrality of the capital's garrison. The committee methodically planned to occupy strategic locations through the city, almost without concealing their preparations: the Provisional Government's president Kerensky was himself aware of them; and some details, leaked by Lev Kamenev and Grigory Zinoviev, were published in newspapers.[21][22]

Onset[edit]

In the early morning of 24 October (O.S.; 6 November N.S.), a group of soldiers loyal to Kerensky's government marched on the printing house of the Bolshevik newspaper, Rabochiy put (Worker's Path), seizing and destroying printing equipment and thousands of newspapers. Shortly thereafter, the government announced the immediate closure of not only Rabochiy put but also the left-wing Soldat, as well as the far-right newspapers Zhivoe slovo and Novaia Rus. The editors and contributors of these newspapers were seen to be calling for insurrection and were to be prosecuted on criminal charges.[23]

In response, at 9 a.m. the Bolshevik Military-Revolutionary Committee issued a statement denouncing the government's actions. At 10 a.m., Bolshevik-aligned soldiers successfully retook the Rabochiy put printing house. Kerensky responded at approximately 3 p.m. that afternoon by ordering the raising of all but one of Petrograd's bridges, a tactic used by the government several months earlier during the July Days. What followed was a series of sporadic clashes over control of the bridges, between Red Guard militias aligned with the Military-Revolutionary Committee and military units still loyal to the government. At approximately 5 p.m. the Military-Revolutionary Committee seized the Central Telegraph of Petrograd, giving the Bolsheviks control over communications through the city.[23][24]

On 25 October (O.S.; 7 November, N.S.) 1917, the Bolsheviks led their forces in the uprising in Petrograd (now St. Petersburg, then capital of Russia) against the Provisional Government. The event coincided with the arrival of a pro-Bolshevik flotilla—consisting primarily of five destroyers and their crews, as well as marines—in Petrograd harbor. At Kronstadt, sailors announced their allegiance to the Bolshevik insurrection. In the early morning, from its heavily guarded and picketed headquarters in Smolny Palace, the Military-Revolutionary Committee designated the last of the locations to be assaulted or seized. The Red Guards systematically captured major government facilities, key communication installations, and vantage points with little opposition. The Petrograd Garrison and most of the city's military units joined the insurrection against the Provisional Government.[22] The insurrection was timed and organized to hand state power to the Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets of Workers' and Soldiers' Deputies, which began on this day.

Kerensky and the Provisional Government were virtually helpless to offer significant resistance. Railways and railway stations had been controlled by Soviet workers and soldiers for days, making rail travel to and from Petrograd impossible for Provisional Government officials. The Provisional Government was also unable to locate any serviceable vehicles. On the morning of the insurrection, Kerensky desperately searched for a means of reaching military forces he hoped would be friendly to the Provisional Government outside the city and ultimately borrowed a Renault car from the American embassy, which he drove from the Winter Palace, along with a Pierce Arrow. Kerensky was able to evade the pickets going up around the palace and to drive to meet approaching soldiers.[23]

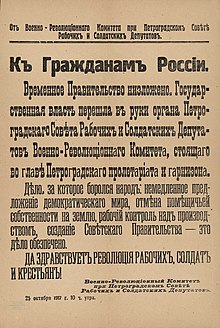

As Kerensky left Petrograd, Lenin wrote a proclamation To the Citizens of Russia, stating that the Provisional Government had been overthrown by the Military-Revolutionary Committee. The proclamation was sent by telegraph throughout Russia, even as the pro-Soviet soldiers were seizing important control centers throughout the city. One of Lenin's intentions was to present members of the Soviet congress, who would assemble that afternoon, with a fait accompli and thus forestall further debate on the wisdom or legitimacy of taking power.[23]

Assault on the Winter Palace[edit]

A final assault against the Winter Palace—against 3,000 cadets, officers, cossacks, and female soldiers—was not vigorously resisted.[23][25] The Bolsheviks delayed the assault because they could not find functioning artillery and acted with restraint to avoid needless violence.[26] At 6:15 p.m., a large group of artillery cadets abandoned the palace, taking their artillery with them. At 8:00 p.m., 200 cossacks left the palace and returned to their barracks.[23]

While the cabinet of the provisional government within the palace debated what action to take, the Bolsheviks issued an ultimatum to surrender. Workers and soldiers occupied the last of the telegraph stations, cutting off the cabinet's communications with loyal military forces outside the city. As the night progressed, crowds of insurgents surrounded the palace, and many infiltrated it.[23] At 9:45 p.m, the cruiser Aurora fired a blank shot from the harbor. Some of the revolutionaries entered the palace at 10:25 p.m. and there was a mass entry 3 hours later.

By 2:10 a.m. on 26 October, Bolshevik forces had gained control. The Cadets and the 140 volunteers of the Women's Battalion surrendered rather than resist the 40,000 strong attacking force.[27][28] After sporadic gunfire throughout the building, the cabinet of the Provisional Government surrendered, and were imprisoned in Peter and Paul Fortress. The only member who was not arrested was Kerensky himself, who had already left the palace.[23][29]

With the Petrograd Soviet now in control of government, garrison, and proletariat, the Second All Russian Congress of Soviets held its opening session on the day, while Trotsky dismissed the opposing Mensheviks and the Socialist Revolutionaries (SR) from Congress.

Dybenko's disputed role[edit]

Some sources contend that as the leader of Tsentrobalt, Pavlo Dybenko played a crucial role in the revolt and that the ten warships that arrived at the city with ten thousand Baltic Fleet mariners were the force that took the power in Petrograd and put down the Provisional Government. The same mariners then dispersed by force the elected parliament of Russia,[30] and used machine-gun fire against demonstrators in Petrograd,[citation needed] killing about 100 demonstrators and wounding several hundred.[citation needed] Dybenko in his memoirs mentioned this event as "several shots in the air". These are disputed by various sources, such as Louise Bryant,[31] who claims that news outlets in the West at the time reported that the unfortunate loss of life occurred in Moscow, not Petrograd, and the number was much less than suggested above. As for the "several shots in the air", there is little evidence suggesting otherwise.

Later Soviet portrayal[edit]

While the seizure of the Winter Palace happened almost without resistance, Soviet historians and officials later tended to depict the event in dramatic and heroic terms.[22][32][33] The historical reenactment titled The Storming of the Winter Palace was staged in 1920. This reenactment, watched by 100,000 spectators, provided the model for official films made later, which showed fierce fighting during the storming of the Winter Palace,[34] although, in reality, the Bolshevik insurgents had faced little opposition.[25]

Later stories of the heroic "Storming of the Winter Palace" and "defense of the Winter Palace" were propaganda by Bolshevik publicists. Grandiose paintings depicting the "Women's Battalion" and photo stills taken from Sergei Eisenstein's staged film depicting the "politically correct" version of the October events in Petrograd came to be taken as truth.[35]

Outcome[edit]

New government established[edit]

The Second Congress of Soviets consisted of 670 elected delegates: 300 were Bolshevik and nearly 100 were Left Socialist-Revolutionaries, who also supported the overthrow of the Alexander Kerensky government.[37] When the fall of the Winter Palace was announced, the Congress adopted a decree transferring power to the Soviets of Workers', Soldiers' and Peasants' Deputies, thus ratifying the Revolution.

The transfer of power was not without disagreement. The center and right wings of the Socialist Revolutionaries, as well as the Mensheviks, believed that Lenin and the Bolsheviks had illegally seized power and they walked out before the resolution was passed. As they exited, they were taunted by Trotsky who told them "You are pitiful isolated individuals; you are bankrupts; your role is played out. Go where you belong from now on — into the dustbin of history!"[38]

The following day, 26 October, the Congress elected a new cabinet of Bolsheviks, pending the convocation of a Constituent Assembly. This new Soviet government was known as the Council (Soviet) of People's Commissars (Sovnarkom), with Lenin as a leader. Lenin allegedly approved of the name, reporting that it "smells of revolution".[39] The cabinet quickly passed the Decree on Peace and the Decree on Land. This new government was also officially called "provisional" until the Assembly was dissolved.

Anti-Bolshevik sentiment[edit]

That same day, posters were pinned on walls and fences by the right-wing Socialist Revolutionaries, describing the takeover as a "crime against the motherland" and "revolution"; this signaled the next wave of anti-Bolshevik sentiment. The next day, the Mensheviks seized power in Georgia and declared it an independent republic; the Don Cossacks also claimed control of their government. The Bolshevik strongholds were in the cities, particularly Petrograd, with support much more mixed in rural areas. The peasant-dominated Left SR party was in coalition with the Bolsheviks. There were reports that the Provisional Government had not conceded defeat and were meeting with the army at the Front.

Anti-Bolshevik sentiment continued to grow as posters and newspapers started criticizing the actions of the Bolsheviks and refuted their authority. The Executive Committee of Peasants Soviets "[refuted] with indignation all participation of the organized peasantry in this criminal violation of the will of the working class".[40] This eventually developed into major counter-revolutionary action, as on 30 October (O.S., 12 November, N.S.) when Cossacks, welcomed by church bells, entered Tsarskoye Selo on the outskirts of Petrograd with Kerensky riding on a white horse. Kerensky gave an ultimatum to the rifle garrison to lay down weapons, which was promptly refused. They were then fired upon by Kerensky's cossacks, which resulted in 8 deaths. This turned soldiers in Petrograd against Kerensky as being the Tsarist regime. Kerensky's failure to assume authority over troops was described by John Reed as a "fatal blunder" that signaled the final end of his government.[41] Over the following days, the battle against the anti-Bolsheviks continued. The Red Guard fought against cossacks at Tsarskoye Selo, with the cossacks breaking rank and fleeing, leaving their artillery behind. On 31 October 1917 (13 November, N.S), the Bolsheviks gained control of Moscow after a week of bitter street-fighting. Artillery had been freely used, with an estimated 700 casualties. However, there was continued support for Kerensky in some of the provinces.

After the fall of Moscow, there was only minor public anti-Bolshevik sentiment, such as the newspaper Novaya Zhizn, which criticized the Bolsheviks' lack of manpower and organization in running their party, let alone a government. Lenin confidently claimed that there is "not a shadow of hesitation in the masses of Petrograd, Moscow and the rest of Russia" in accepting Bolshevik rule.[42]

Governmental reforms[edit]

On 10 November 1917 (23 November, N.S.), the government applied the term "citizens of the Russian Republic" to Russians, whom they sought to make equal in all possible respects, by the nullification of all "legal designations of civil inequality, such as estates, titles, and ranks."[43]

The long-awaited Constituent Assembly elections were held on 12 November (O.S., 25 November, N.S.) 1917. In contrast to their majority in the Soviets, the Bolsheviks only won 175 seats in the 715-seat legislative body, coming in second behind the Socialist Revolutionary Party, which won 370 seats, although the SR Party no longer existed as a whole party by that time, as the Left SRs had gone into coalition with the Bolsheviks from October 1917 to March 1918 (a cause of dispute of the legitimacy of the returned seating of the Constituent Assembly, as the old lists, were drawn up by the old SR Party leadership, and thus represented mostly Right SRs, whereas the peasant soviet deputies had returned majorities for the pro-Bolshevik Left SRs). The Constituent Assembly was to first meet on 28 November (O.S.) 1917, but its convocation was delayed until 5 January (O.S.; 18 January, N.S.) 1918 by the Bolsheviks. On its first and only day in session, the Constituent Assembly came into conflict with the Soviets, and it rejected Soviet decrees on peace and land, resulting in the Constituent Assembly being dissolved the next day by order of the Congress of Soviets.[44]

On 16 December 1917 (29 December, N.S.), the government ventured to eliminate hierarchy in the army, removing all titles, ranks, and uniform decorations. The tradition of saluting was also eliminated.[43]

On 20 December 1917 (2 January 1918, N.S.), the Cheka was created by Lenin's decree.[45] These were the beginnings of the Bolsheviks' consolidation of power over their political opponents. The Red Terror began in September 1918, following a failed assassination attempt on Lenin. The French Jacobin Terror was an example for the Soviet Bolsheviks. Trotsky had compared Lenin to Maximilien Robespierre as early as 1904.[46]

The Decree on Land ratified the actions of the peasants who throughout Russia had taken private land and redistributed it among themselves. The Bolsheviks viewed themselves as representing an alliance of workers and peasants signified by the Hammer and Sickle on the flag and the coat of arms of the Soviet Union. Other decrees:

- All private property was nationalized by the government.

- All Russian banks were nationalized.

- Private bank accounts were expropriated.

- The properties of the Russian Orthodox Church (including bank accounts) were expropriated.

- All foreign debts were repudiated.

- Control of the factories was given to the soviets.

- Wages were fixed at higher rates than during the war, and a shorter, eight-hour working day was introduced.

Timeline of the spread of Soviet power (Gregorian calendar dates)[edit]

- 5 November 1917: Tallinn.

- 7 November 1917: Petrograd, Minsk, Novgorod, Ivanovo-Voznesensk and Tartu

- 8 November 1917: Ufa, Kazan, Yekaterinburg, and Narva; (failed in Kiev)

- 9 November 1917: Vitebsk, Yaroslavl, Saratov, Samara, and Izhevsk

- 10 November 1917: Rostov, Tver, and Nizhny Novgorod

- 12 November 1917: Voronezh, Smolensk, and Gomel

- 13 November 1917: Tambov

- 14 November 1917: Orel and Perm

- 15 November 1917: Pskov, Moscow, and Baku

- 27 November 1917: Tsaritsyn

- 1 December 1917: Mogilev

- 8 December 1917: Vyatka

- 10 December 1917: Kishinev

- 11 December 1917: Kaluga

- 14 December 1917: Novorossisk

- 15 December 1917: Kostroma

- 20 December 1917: Tula

- 24 December 1917: Kharkov (invasion of Ukraine by the Muravyov Red Guard forces, the establishment of Soviet Ukraine and hostilities in the region)

- 29 December 1917: Sevastopol (invasion of Crimea by the Red Guard forces, the establishment of the Taurida Soviet Socialist Republic)

- 4 January 1918: Penza

- 11 January 1918: Yekaterinoslav

- 17 January 1918: Petrozavodsk

- 19 January 1918: Poltava

- 22 January 1918: Zhitomir

- 26 January 1918: Simferopol

- 27 January 1918: Nikolayev

- 28 January 1918: Helsinki (the Reds overthrow the White Senate, the Finnish Civil War begins)

- 29 January 1918: (failed again in Kiev)

- 31 January 1918: Odessa and Orenburg (establishment of the Odessa Soviet Republic)

- 7 February 1918: Astrakhan

- 8 February 1918: Kiev and Vologda (defeat of the Ukrainian government)

- 17 February 1918: Arkhangelsk

- 25 February 1918: Novocherkassk

Russian Civil War[edit]

Bolshevik-led attempts to gain power in other parts of the Russian Empire were largely successful in Russia proper—although the fighting in Moscow lasted for two weeks—but they were less successful in ethnically non-Russian parts of the Empire, which had been clamoring for independence since the February Revolution. For example, the Ukrainian Rada, which had declared autonomy on 23 June 1917, created the Ukrainian People's Republic on 20 November, which was supported by the Ukrainian Congress of Soviets. This led to an armed conflict with the Bolshevik government in Petrograd and, eventually, a Ukrainian declaration of independence from Russia on 25 January 1918.[47] In Estonia, two rival governments emerged: the Estonian Provincial Assembly, established in April 1917, proclaimed itself the supreme legal authority of Estonia on 28 November 1917 and issued the Declaration of Independence on 24 February 1918;[48] but Soviet Russia recognized the Executive Committee of the Soviets of Estonia as the legal authority in the province, although the Soviets in Estonia controlled only the capital and a few other major towns.[49]

After the success of the October Revolution transformed the Russian state into a soviet republic, a coalition of anti-Bolshevik groups attempted to unseat the new government in the Russian Civil War from 1918 to 1922. In an attempt to intervene in the civil war after the Bolsheviks' separate peace with the Central Powers, the Allied Powers (the United Kingdom, France, Italy, the United States, and Japan) occupied parts of the Soviet Union for over two years before finally withdrawing.[50] The United States did not recognize the new Russian government until 1933. The European powers recognized the Soviet Union in the early 1920s and began to engage in business with it after the New Economic Policy (NEP) was implemented.[citation needed]

Historiography[edit]

| Part of a series on |

| Marxism–Leninism |

|---|

|

Historical research into few events has been as influenced by the researcher's political outlook as that of the October Revolution.[51] The historiography of the Revolution generally divides into three camps: Soviet-Marxist, Western-Totalitarian, and Revisionist.[52]

Soviet historiography[edit]

Soviet historiography of the October Revolution is intertwined with Soviet historical development. Many of the initial Soviet interpreters of the Revolution were themselves Bolshevik revolutionaries.[53] After the initial wave of revolutionary narratives, Soviet historians worked within "narrow guidelines" defined by the Soviet government. The rigidity of interpretive possibilities reached its height under Stalin.[54]

Soviet historians of the Revolution interpreted the October Revolution as being about establishing the legitimacy of Marxist ideology and the Bolshevik government. To establish the accuracy of Marxist ideology, Soviet historians generally described the Revolution as the product of class struggle and that it was the supreme event in a world history governed by historical laws. The Bolshevik Party is placed at the center of the Revolution, as it exposes the errors of both the moderate Provisional Government and the spurious "socialist" Mensheviks in the Petrograd Soviet. Guided by Lenin's leadership and his firm grasp of scientific Marxist theory, the Party led the "logically predetermined" events of the October Revolution from beginning to end. The events were, according to these historians, logically predetermined because of the socio-economic development of Russia, where monopolistic industrial capitalism had alienated the masses. In this view, the Bolshevik party took the leading role in organizing these alienated industrial workers, and thereby established the construction of the first socialist state.[55]

Although Soviet historiography of the October Revolution stayed relatively constant until 1991, it did undergo some changes. Following Stalin's death, historians such as E. N. Burdzhalov and P. V. Volobuev published historical research that deviated significantly from the party line in refining the doctrine that the Bolshevik victory "was predetermined by the state of Russia's socio-economic development".[56] These historians, who constituted the "New Directions Group", posited that the complex nature of the October Revolution "could only be explained by a multi-causal analysis, not by recourse to the mono-causality of monopoly capitalism".[57] For them, the central actor is still the Bolshevik party, but this party triumphed "because it alone could solve the preponderance of 'general democratic' tasks the country faced" (such as the struggle for peace and the exploitation of landlords).[58]

During the late Soviet period, the opening of select Soviet archives during glasnost sparked innovative research that broke away from some aspects of Marxism–Leninism, though the key features of the orthodox Soviet view remained intact.[54]

Following the turn of the 21st century, some Soviet historians began to implement an "anthropological turn" in their historiographical analysis of the Russian Revolution. This method of analysis focuses on the average person's experience of day-to-day life during the revolution, and pulls the analytical focus away from larger events, notable revolutionaries, and overarching claims about party views.[59] In 2006, S. V. Iarov employed this methodology when he focused on citizen adjustment to the new Soviet system. Iarov explored the dwindling labor protests, evolving forms of debate, and varying forms of politicization as a result of the new Soviet rule from 1917 to 1920.[60] In 2010, O. S. Nagornaia took interest in the personal experiences of Russian prisoners-of-war taken by Germany, examining Russian soldiers and officers' ability to cooperate and implement varying degrees of autocracy despite being divided by class, political views, and race.[61] Other analyses following this "anthropological turn" have explored texts from soldiers and how they used personal war-experiences to further their political goals,[62] as well as how individual life-structure and psychology may have shaped major decisions in the civil war that followed the revolution.[63]

Western historiography[edit]

During the Cold War, Western historiography of the October Revolution developed in direct response to the assertions of the Soviet view. As a result, Western historians exposed what they believed were flaws in the Soviet view, thereby undermining the Bolsheviks' original legitimacy, as well as the precepts of Marxism.[64]

These Western historians described the revolution as the result of a chain of contingent accidents. Examples of these accidental and contingent factors they say precipitated the Revolution included World War I's timing, chance, and the poor leadership of Tsar Nicholas II as well as that of liberal and moderate socialists.[54] According to Western historians, it was not popular support, but rather a manipulation of the masses, ruthlessness, and the party discipline of the Bolsheviks that enabled their triumph. For these historians, the Bolsheviks' defeat in the Constituent Assembly elections of November–December 1917 demonstrated popular opposition to the Bolsheviks' revolution, as did the scale and breadth of the Civil War.[65]

Western historians saw the organization of the Bolshevik party as proto-totalitarian. Their interpretation of the October Revolution as a violent coup organized by a proto-totalitarian party reinforced for them the idea that totalitarianism was an inherent part of Soviet history. The democratic promise of the February Revolution came to an end with the forced dissolution of the Constituent Assembly.[66] Thus, Stalinist totalitarianism developed as a natural progression from Leninism and the Bolshevik party's tactics and organization.[67]

Effect of the dissolution of the Soviet Union on historical research[edit]

The dissolution of the Soviet Union affected historical interpretations of the October Revolution. Since 1991, increasing access to large amounts of Soviet archival materials has made it possible to re‑examine the October Revolution.[53] Though both Western and Russian historians now have access to many of these archives, the effect of the dissolution of the USSR can be seen most clearly in the work of the latter. While the disintegration essentially helped solidify the Western and Revisionist views, post-USSR Russian historians largely repudiated the former Soviet historical interpretation of the Revolution.[68] As Stephen Kotkin argues, 1991 prompted "a return to political history and the apparent resurrection of totalitarianism, the interpretive view that, in different ways…revisionists sought to bury".[53]

Legacy[edit]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2018) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

The October Revolution marks the inception of the first communist government in Russia, and thus the first large-scale and constitutionally ordained socialist state in world history. After this, the Russian Republic became the Russian SFSR and, later form the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics.

The October Revolution also made the ideology of communism influential on a global scale in the 20th century. Communist parties would start to form in many countries after 1917.

Ten Days That Shook the World, a book written by American journalist John Reed and first published in 1919, gives a firsthand exposition of the events. Reed died in 1920, shortly after the book was finished.

Dmitri Shostakovich wrote his Symphony No. 2 in B major, Op. 14, and subtitled it To October, for the 10th anniversary of the October Revolution. The choral finale of the work, "To October", is set to a text by Alexander Bezymensky, which praises Lenin and the revolution. The Symphony No. 2 was first performed on 5 November 1927 by the Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra and the Academy Capella Choir under the direction of Nikolai Malko.

Sergei Eisenstein and Grigori Aleksandrov's film October: Ten Days That Shook the World, first released on 20 January 1928 in the USSR and on 2 November 1928 in New York City, describes and glorifies the revolution, having been commissioned to commemorate the event.

The term "Red October" (Красный Октябрь, Krasnyy Oktyabr) has been used to signify the October Revolution. "Red October" was given to a steel factory that was made notable by the Battle of Stalingrad,[69] a Moscow sweets factory that is well known in Russia, and a fictional Soviet submarine in both Tom Clancy's 1984 novel The Hunt for Red October and the 1990 film adaptation of the same name.

7 November, the anniversary of the October Revolution according to the Gregorian Calendar, was the official national day of the Soviet Union from 1918 onward and still is a public holiday in Belarus and the breakaway territory of Transnistria. Communist parties both in and out of power celebrate November 7 as the date Marxist parties began to take power.

See also[edit]

- February Revolution

- Ten Days That Shook the World

- Revolutions of 1917–1923

- Russian Civil War

- Russian Revolution (1917)

- Kiev Bolshevik Uprising

- Dissolution of the Soviet Union (1991)

- October Revolution Day

- Index of articles related to the Russian Revolution and Civil War

- Bibliography of the Russian Revolution and Civil War

Notes[edit]

- ^ Russian: Октябрьская революция, tr. Oktyabrskaya revolyutsiya, IPA: [ɐkˈtʲabrʲskəjə rʲɪvɐˈlʲutsɨjə].

- ^ Officially known in Soviet historiography as the Great October Socialist Revolution (Russian: Великая Октябрьская социалистическая революция, tr. Velikaya Oktyabrskaya sotsialisticheskaya revolyutsiya).

Citations[edit]

- ^ "Russian Revolution". history.com. 9 November 2009.

- ^ Samaan, A.E. (2 February 2013). From a "Race of Masters" to a "Master Race": 1948 to 1848. A.E. Samaan. p. 346. ISBN 978-0615747880. Retrieved 9 February 2017.

- ^ "Russian Revolution - Causes, Timeline & Definition - HISTORY". www.history.com. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- ^ "Russian Revolution | Definition, Causes, Summary, History, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- ^ Bunyan & Fisher 1934, p. 385.

- ^ a b Steinberg, Mark (2017). The Russian Revolution 1905-1917. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 143–146. ISBN 978-0-19-922762-4.

- ^ Mandel, David (1984). The Petrograd workers and the Soviet seizure of power : from the July days, 1917 to July 1918. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-60395-3. OCLC 9682585.

- ^ Trotsky, Leon (1934). History of the Russian Revolution. London: The Camelot Press ltd. pp. 859–864.

- ^ Steinberg, Mark (2017). The Russian Revolution, 1905-1921. Oxford New York, NY: Oxford University Press. pp. 196–197. ISBN 978-0-19-922762-4. OCLC 965469986.

- ^ Upton, Anthony F. (1980). The Finnish Revolution: 1917-1918. Minneapolis, Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press. p. 89. ISBN 9781452912394.

- ^ Steinberg, Mark D. (2017). The Russian Revolution 1905-1921. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. pp. 191, 193–194. ISBN 9780199227624.

- ^ Richard Pipes (1990). The Russian Revolution. Knopf Doubleday. p. 407. ISBN 9780307788573.

- ^ Kort, Michael (1993). The Soviet colossus : the rise and fall of the USSR. Armonk, N.Y: M.E. Sharpe. p. 104. ISBN 978-0-87332-676-6.

- ^ Michael C. Hickey (2010). Competing Voices from the Russian Revolution: Fighting Words: Fighting Words. ABC-CLIO. p. 559. ISBN 9780313385247.

- ^ Beckett 2007, p. 526

- ^ Pipes 1997, p. 51: "There is no evidence of a Kornilov plot, but there is plenty of evidence of Kerensky's duplicity."

- ^ Service 2005, p. 54

- ^ "How Germany got the Russian Revolution off the ground". Deutsche Welle. 7 November 2017.

- ^ "Central Committee Meeting—10 Oct 1917".

- ^ Steinberg, Mark (2001). Voices of the Revolution, 1917. Binghamton, New York: Yale University Press. p. 170. ISBN 0300090161.

- ^ "1917 – La Revolution Russe". Arte TV. 16 September 2007. Archived from the original on 1 February 2016. Retrieved 25 January 2016.

- ^ a b c Suny, Ronald (2011). The Soviet Experiment. Oxford University Press. pp. 63–67.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Rabinowitch 2004, pp. 273–305

- ^ Bard College: Experimental Humanities and Eurasian Studies. "From Empire To Republic: October 24 – November 1, 1917". Retrieved 24 February 2018.

- ^ a b Beckett 2007, p. 528

- ^ Rabinowitch 2004

- ^ Lynch, Michael (2015). Reaction and revolution : Russia 1894-1924 (4th ed.). London England: Hodder Education. ISBN 978-1-4718-3856-9. OCLC 908064756.

- ^ Raul Edward Chao (2016). Damn the Revolution!. Washington DC, London, Sydney: Dupont Circle Editions. p. 191.

- ^ "1917 Free History". Yandex Publishing. Archived from the original on 8 November 2017. Retrieved 8 November 2017.

- ^ "ВОЕННАЯ ЛИТЕРАТУРА --[ Мемуары ]-- Дыбенко П.Е. Из недр царского флота к Великому Октябрю". militera.lib.ru (in Russian).

- ^ Louise Bryant (1918). Six Red Months in Russia. George H. Doran Company. pp. 60–61.

- ^ Jonathan Schell, 2003. 'The Mass Minority in Action: France and Russia'. For example, in The Unconquerable World.London: Penguin, pp. 167–185.

- ^ (See a first-hand account by British General Knox.)

- ^ Sergei M. Eisenstein; Grigori Aleksandrov (1928). October (Ten Days that Shook the World) (Motion picture). First National Pictures.

- ^ Argumenty i Fakty newspaper

- ^ "The Constituent Assembly". jewhistory.ort.spb.ru.

- ^ Service, Robert (1998). A history of twentieth-century Russia. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-40347-9 p 65

- ^ Reed 1997, p. 217

- ^ Steinberg, Mark D. (2001). Voices of Revolution, 1917. Yale University. p. 251. ISBN 978-0300101690.

- ^ Reed 1997, p. 369

- ^ Reed 1997, p. 410

- ^ Reed 1997, p. 565

- ^ a b Steinberg, Mark D. (2001). Voices of Revolution. Yale University. p. 257.

- ^ Jennifer Llewellyn, John Rae, and Steve Thompson (2014). "The Constituent Assembly". Alpha History.

- ^ Figes, 1996.

- ^ Richard Pipes: The Russian Revolution

- ^ See Encyclopedia of Ukraine online

- ^ Miljan, Toivo. "Historical Dictionary of Estonia." Historical Dictionary of Estonia, Rowman & Littlefield, 2015, p. 169

- ^ Raun, Toivo U. "The Emergence of Estonian Independence 1917-1920." Estonia and the Estonians, Hoover Inst. Press, 2002, p. 102

- ^ Ward, John (2004). With the "Die-Hards" in Siberia. Dodo Press. p. 91. ISBN 1409906809.

- ^ Acton 1997, p. 5

- ^ Acton 1997, pp. 5–7

- ^ a b c Kotkin, Stephen (1998). "1991 and the Russian Revolution: Sources, Conceptual Categories, Analytical Frameworks". The Journal of Modern History. University of Chicago Press. 70 (2): 384–425. doi:10.1086/235073. ISSN 0022-2801. S2CID 145291237.

- ^ a b c Acton 1997, p. 7

- ^ Acton 1997, p. 8

- ^ Alter Litvin, Writing History in Twentieth-Century Russia, (New York: Palgrave, 2001), 49–50.

- ^ Roger Markwick, Rewriting History in Soviet Russia: The Politics of Revisionist Historiography, (New York: Palgrave, 2001), 97.

- ^ Markwick, Rewriting History, 102.

- ^ Smith, S. A. (2015). "The historiography of the Russian Revolution 100 Years On". Kritika: Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History. 16 (4): 733–749. doi:10.1353/kri.2015.0065. S2CID 145202617.

- ^ Iarov, S.V. (2006). "Konformizm v Sovetskoi Rossii: Petrograd, 1917-20". Evropeiskii Dom (in Russian).

- ^ Nagornaia, O. S. (2010). "Drugoi voennyi opyt: Rossiiskie voennoplennye Pervoi mirovoi voiny v Germanii (1914-1922)". Novyi Khronograf (in Russian).

- ^ Morozova, O. M. (2010). "Dva akta dreamy: Boevoe proshloe I poslevoennaia povsednevnost ' veteran grazhdanskoi voiny". Rostov-on-Don: Iuzhnyi Nauchnyi Tsentr Rossiiskoi Akademii Nauk (in Russian).

- ^ O. M., Morozova (2007). "Antropologiia grazhdanskoi voiny". Rostov-on-Don: Iuzhnyi Nauchnyi Tsentr RAN (in Russian).

- ^ Acton 1997, pp. 6–7

- ^ Acton 1997, pp. 7–9

- ^ Norbert Francis, "Revolution in Russia and China: 100 Years," International Journal of Russian Studies 6 (July 2017): 130-143.

- ^ Stephen E. Hanson (1997). Time and Revolution: Marxism and the Design of Soviet Institutions. U of North Carolina Press. p. 130. ISBN 9780807846155.

- ^ Litvin, Alter, Writing History, 47.

- ^ Ivanov, Mikhail (2007). Survival Russian. Montpelier, VT: Russian Life Books. p. 44. ISBN 978-1-880100-56-1. OCLC 191856309.

References[edit]

- Acton, Edward (1997). Critical Companion to the Russian Revolution.

- Ascher, Abraham (2014). The Russian Revolution: A Beginner's Guide. Oneworld Publications.

- Beckett, Ian F. W. (2007). The Great war (2 ed.). Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-1252-8.

- Bone, Ann (trans.) (1974). The Bolsheviks and the October Revolution: Central Committee Minutes of the Russian Social-Democratic Labour Party (Bolsheviks) August 1917-February 1918. Pluto Press. ISBN 0-902818546.

- Bunyan, James; Fisher, Harold Henry (1934). The Bolshevik Revolution, 1917–1918: Documents and Materials. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press. OCLC 253483096.

- Chamberlin, William Henry (1935). The Russian Revolution. I: 1917–1918: From the Overthrow of the Tsar to the Assumption of Power by the Bolsheviks. Old Classic.

- Figes, Orlando (1996). A People's Tragedy: The Russian Revolution: 1891–1924. Pimlico. ISBN 9780805091311. online free to borrow

- Guerman, Mikhail (1979). Art of the October Revolution.

- Kollontai, Alexandra (1971). "The Years of Revolution". The Autobiography of a Sexually Emancipated Communist Woman. New York: Herder and Herder. OCLC 577690073.

- Krupskaya, Nadezhda (1930). "The October Days". Reminiscences of Lenin. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House. OCLC 847091253.

- Luxemburg, Rosa (1940) [1918]. The Russian Revolution. Translated by Bertram Wolfe. New York City: Workers Age. OCLC 579589928.

- Mandel, David (1984). The Petrograd Workers and the Soviet seizure of power. London: MacMillan.

- Pipes, Richard (1997). Three "whys" of the Russian Revolution. Vintage Books. ISBN 978-0-679-77646-8.

- Rabinowitch, Alexander (2004). The Bolsheviks Come to Power: The Revolution of 1917 in Petrograd. Pluto Press. ISBN 9780745322681.

- Radek, Karl (1995) [First published 1922 as "Wege der Russischen Revolution"]. "The Paths of the Russian Revolution". In Bukharin, Nikolai; Richardson, Al (eds.). In Defence of the Russian Revolution: A Selection of Bolshevik Writings, 1917–1923. London: Porcupine Press. pp. 35–75. ISBN 1899438017. OCLC 33294798.

- Read, Christopher (1996). From Tsars to Soviets.

- Reed, John (1997) [1919]. Ten Days that Shook the World. New York: St. Martin's Press.

- Serge, Victor (1972) [1930]. Year One of the Russian Revolution. London: Penguin Press. OCLC 15612072.

- Service, Robert (1998). A history of twentieth-century Russia. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-40347-9.

- Shukman, Harold, ed. (1998). The Blackwell Encyclopedia of the Russian Revolution.

articles by over 40 specialists

- Swain, Geoffrey (2014). Trotsky and the Russian Revolution. Routledge.

- Trotsky, Leon (1930). "XXVI: FROM JULY TO OCTOBER". My Life. London: Thornton Butterworth. OCLC 181719733.

- Trotsky, Leon (1932). The History of the Russian Revolution. III. Translated by Max Eastman. London: Gollancz. OCLC 605191028.

- Wade, Rex A. "The Revolution at One Hundred: Issues and Trends in the English Language Historiography of the Russian Revolution of 1917." Journal of Modern Russian History and Historiography 9.1 (2016): 9-38. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1163/22102388-00900003

Comments